YAŞAR ADANALI

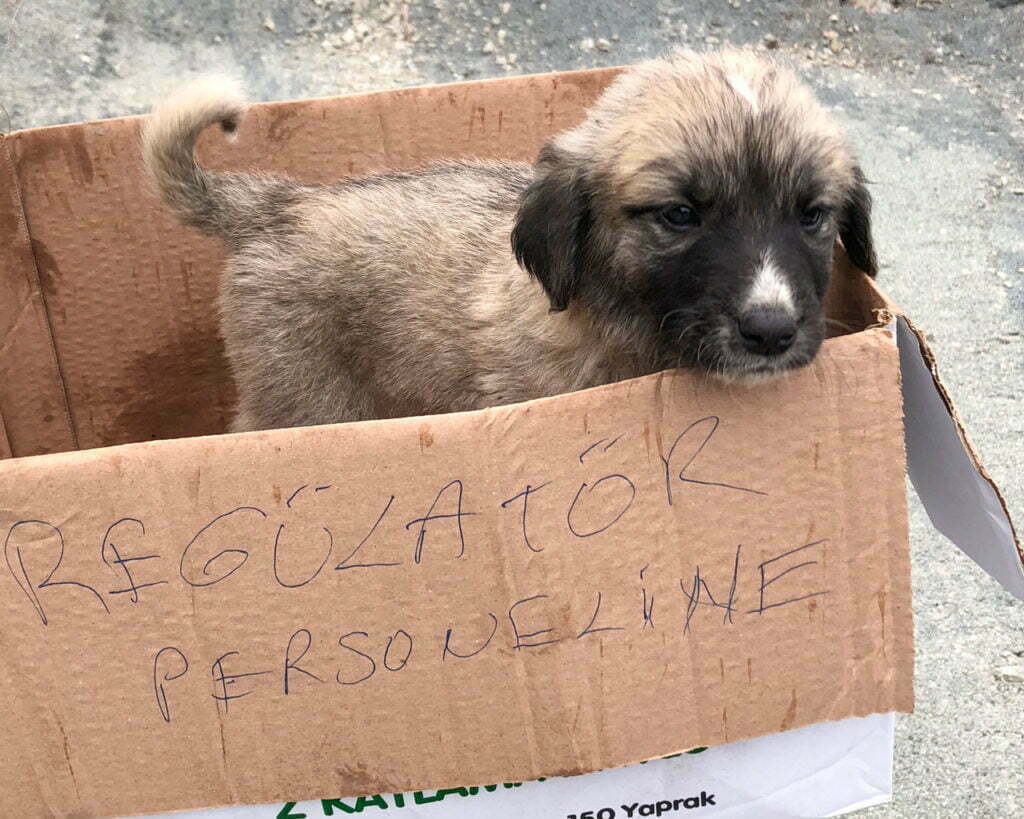

Among the most disconcerting sights of our two-day journey from the point where the Melet meets the Black Sea to the river source were the abandoned strays that would meet us at every stop along the way. We saw dozens of dogs rounded up from the Ordu town center and banished to hydroelectric power plant (HEPP) and road construction sites all along the Melet Basin. They were all in poor condition, all hungry and forlorn. And they all had tags affixed to their ears by the municipality. Clearly, this deportation of dogs was no arbitrary event but the result of local administrative action. While the stone quarries and road construction sites stretching parallel to the valley have joined forces with the HEPPs cutting across it to turn the Melet Basin into a grey landscape, it seems that dogs have been cast out right at the locations where this devastation is most intensely palpable.

For our team coming from Istanbul, this encounter was as familiar as it was jarring. We know all too well how dogs are being rounded up from the central districts of Istanbul, rapidly changing at the hands of urban transformation projects, only to be discarded at the city’s peripheries and abandoned to their fate. On the flip side of this same trend are the relentless incursion of megaprojects into urban forests and public gardens. The number of abandoned dogs rises in tandem with the proliferation of yellow dump trucks and grey construction zones in an ecosystem that was once populated by trees, wetlands, water buffaloes, and birds.

Though the mistaken assumption that “Dogs are animals after all, and can survive anywhere in nature, away from humans,” has lost traction, there are still people who think this way. So let’s be clear: Dogs are domesticated animals. They live with humans, in human habitats. Historically, they have been the staples of urban life, and therefore, they too have a right to the cities of Turkey. Municipalities must return these stray animals to wherever they feel at home after providing them with the necessary care and treatment.

“The Making of a Dogless Istanbul” has been one of our focal issues in the last two years of the “Urban Political Ecology Summer School on the Roads of Istanbul” organized by the Center for Spatial Justice. We invited animal rights activist Mine Yıldırım, who wrote her PhD dissertation on this issue. She shared with us the work they do as the Four-Legged City (Dört Ayaklı Şehir) collective started by her and her friends. The collective has come together with the aim of “providing snapshots of the lives of Istanbul’s stray animals, bearing witness to them, and most of all to document the history of the nefarious acts these animals have been subjected to and keep a ‘criminal record’ of the city’s many anonymous crimes against them.”

In our journey to keep an “environmental criminal record” of how Melet’s extraordinary natural landscape is being ravaged by HEPPs, stone quarries, and large-scale projects, we found ourselves confronted with crimes committed against Ordu’s dogs as well. Spatial justice is, after all, a must for all creatures – whether two or four-legged.