SİNAN ERENSÜ

Statistics lie as much as they tell the truth, but let them go ahead and do that. Sometimes tracing a lie allows us to uncover an unspoken truth.

One such “false-truth” is regarding Artvin and its share in public investments. This remote province, a backwater beyond the mental maps of many, stuck in a far corner of Turkey is one of the places that report some of the highest shares in public investments. This is not even a one or two-year blip. The government has regularly been pouring a fortune into Artvin for the past 15 years, working towards its development and prosperity.

Let’s have a look at the provincial distribution of investments in Turkey. The province with the greatest share is the same every year: Istanbul. This, of course, does not come as a surprise. A fifth of the country’s population lives in Istanbul. The city’s share in the gross domestic product (GDP) is above 30%. It is therefore understandable that Istanbul receives a good chunk of public funding. Following this logic, we would not expect Artvin, which is the seventh (and in some years sixth) least populated province among the 81 provinces, and contributes less than 0.4% to the GDP to have much access to public investments. However, contrary to expectations, Artvin is at the top of the list of provinces attracting the highest amounts of public investment on a regular basis since the early 2000s. We see Artvin coming in second after Istanbul and Ankara in 2003, fifth in 2006 and 2010, third in 2012, and tenth in 2018.

For instance, in 2012, Artvin became the province to receive the highest amount of public funding after Ankara and Istanbul with 849 million 704 thousand TL. If we are to think of it relatively, 40 liras out of every 1000 spent from the state’s pocket has been allocated to Artvin, which is home to only two out of every thousand people living in the country. How wonderful, right?

When we calculate what these investments amount to per person, we see just how lucky the people of Artvin are in comparison to the rest of our citizens living in other provinces. Artvin is by far the most fortunate province in terms of public investments per capita in the past 15 years, rarely leaving first place to others in the race to attract public funding. For instance, between the years of 2002 and 2012, the state spent an annual average of 387 TL in investments per citizen, while for the people of Artvin this figure sits at 2811 TL. Meaning that ever since 2002, the people of Artvin have received about seven times as much attention as the average in the rest of Turkey… Our state, being magnanimous, didn’t neglect it for being a faraway border town, with a small population, inhospitable mountainous territory, and only two representatives in parliament; instead, it flooded Artvin with investments.

You must think all of this investing must have definitely made a significant impact on Artvin, assuming perhaps that the province progressed and developed, prospered, and became a place where everyone wanted to live, therefore home to a rapidly growing population. But sadly, this is far from the truth. The Laz, Hemshin, Georgians, Bosha, and Turks of Artvin must not have liked all of these investments, this major leap in development, since they kept moving to metropolises such as Istanbul and Bursa to eke out a living. Today, 64% of Artvin’s registered population resides outside Artvin. In this period where public investments in the province are peaking, we see the population of Artvin both decline and age. For instance, while Artvin was an investment champion from 2007 to 2012, it lost an average of 5.4% of its population annually. Of course, there will be those who argue that such a move for development will take time to show its positive effects. Yet for some reason, TurkStat (the Turkish Statistical Institute) has not partaken in this optimistic view: While it estimates that the population of Turkey will increase by 10% until the year 2023, it has predicted that the population of Artvin will shrink by 3%.

How is it that all of this investment, all of this effort to develop simply cannot keep the people of Artvin in their province? To find the reason for this sharp contradiction, we must of course look not to the ingratitude of the people of Artvin, but to the kind of public investment and the nature of the goal defined as “development” in Turkey.

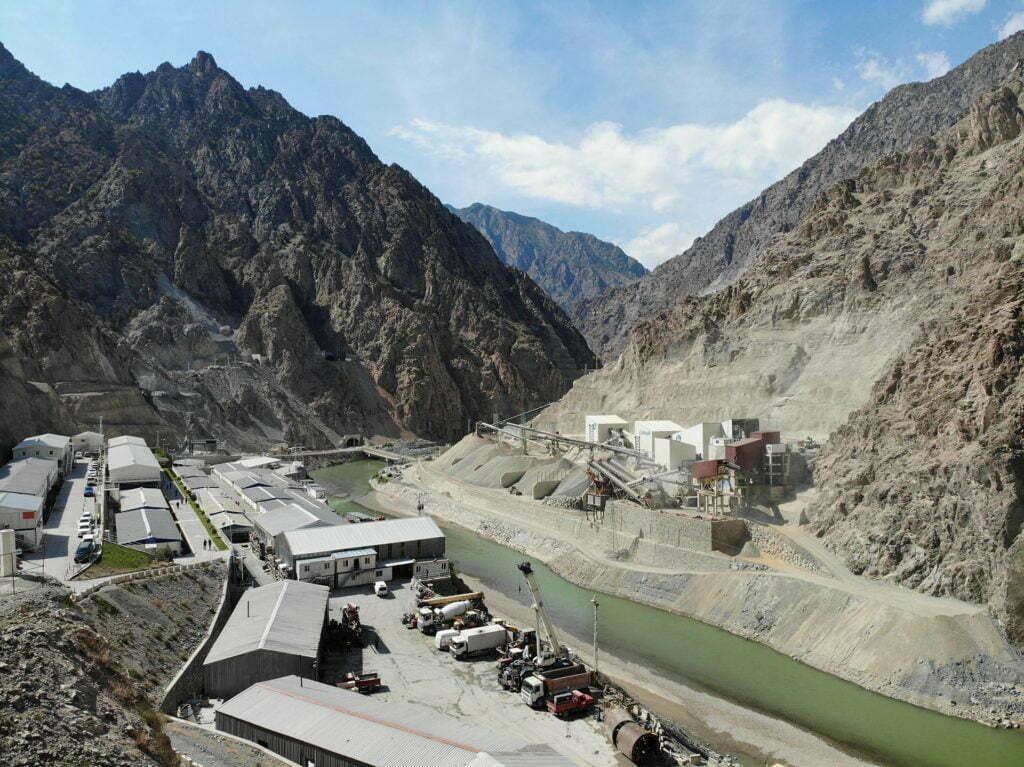

The only reason why Artvin consistently remains on top of development and investment lists is that it has strong rivers that give it its character, streams that gush out in every corner, valleys carved out by them, and mountains containing valuable ores. At the heart of these public investments is the Çoruh River – the unique symbol of all of the province’s natural wealth. This transboundary river that was left untouched out of fear of causing problems until the Soviet Union fell has become a focal point of investments since the 1990s. The Muratlı Dam and Borçka came into operation in 2005 and the Deriner Dam in 2012. Six of the thirteen dams planned to be constructed on the Çoruh, one of the world’s fastest-flowing rivers, lie within the province of Artvin. It is precisely these dams that are the address and recipient of the record-setting investments flowing into the province.

About 90% of the investments in Artvin are spent on the construction of dams, expropriation costs for the villages and agricultural land submerged by dams, and the rebuilding of roads and viaducts swallowed by reservoir lakes. Though these mega investment projects contribute to illuminating shopping malls in the big cities, supplying power to outmoded high-energy industries, and boosting abstract growth levels that don’t have much to do with our lives, they simply aren’t able to keep the people of the lands they mushroom across in Artvin. Providing employment opportunities to a relatively small number of people for a short period of time in low-profile or menial jobs, these investments not only fail to create long-term employment, but they have the opposite effect by altering the climate and impoverishing agricultural fields and crop diversity, which results in wrecking the regional environment and expediting its depopulation.

This aggressive rush of development and investment that is depopulating Artvin and causing an ecocide is not just limited to public investments or large-scale dams. While some of these mega dams are overseen by the State Hydraulic Works (DSI), the relatively more profitable ones belong to the Doğuş Group and the infamous Limak-Cengiz-Kolin trio. If we count the smaller-scale, run-of-the-river hydroelectric power plants (HEPPs), the number of HEPPs planned for construction in Artvin is 124 – which puts it in second place after Trabzon in terms of the distribution of HEPPs per province. Artvin is the apple of the eye of the mining sector as much as it is of the energy sector. The mine that threatens the Artvin center, which was stopped thanks to a 20-year-long struggle but has been operated by the Cengiz Group since 2017, is but one of the mining permit areas that number hundreds in the region. According to data on the Eastern Black Sea region (TR90), where Artvin is located, a portion as substantial as 77.4% of private investments in the area is in the energy and mining sectors.

The road that begins by the seaside in Hopa, passing through Borçka and then the Artvin center to reach Yusufeli and eventually the Erzurum provincial border is one of the three or four main axes connecting the Eastern Black Sea to Anatolia and is without exaggeration Turkey’s most intriguing route. Along this road, it is possible to experience the near-tropical climate on the foothills of the Kaçkars and Karçals, the temperate valleys of Artvin and Barhal, the barren yet imposing slopes of Yusufeli, followed by the majestic plains of Erzurum – one after the other, all in the space of a couple of hours. If you were to listen carefully, you could encounter four or five different languages, and ruminate over the metaphorical meaning of a “mosaic.” More and more rapidly, however, the Artvin landscape has come to resemble one big construction site.

This landscape that Artviners are passionately attached to, yet complicates their lives, is now being conquered through successive developmental ventures. Yet the irony here is that the conquest of this landscape doesn’t benefit the people of Artvin but the investor and those indirectly profiting from the investment. The tragicomic aspect of this is that the electricity consumption per capita in Artvin, seemingly the receiving end of all of these dazzling energy investments, falls far below the national average, and the province ranks thirteenth from the bottom of the list of 81 provinces in terms of the percentage of households heated by radiators. If these dams, viaducts, bridges, and mines are a hallmark of the New Turkey, development is unequal and unjust in the New Turkey as well.

A version of this article has previously been published on the issue dated June 29, 2014, of the Evrensel newspaper.