SİNAN ERENSÜ

Artvin harbors very valuable lessons, questions, and areas of debate for the growing environmental, urban, and ecological agenda in this last decade

The twenty-five-year-old anti-mining movement in Artvin is the longest-running local environmental struggle in this country. Over the course of this quarter of a century witnessing temporary defeats as much as victories, the people of Artvin have managed to chase out every foreign and domestic company seeking to extract ore in Cerattepe. Though the situation appears far from promising since the summer of 2019 when this article was penned and mining operations continue in Cerattepe, it is neither possible to say that the struggle in Artvin has petered out nor are we out of lessons to learn from this struggle. Quite on the contrary, Artvin harbors very valuable lessons, questions, and areas of debate for the growing environmental, urban, and ecological agenda (easily suppressed under an authoritarian wave) in this last decade. Place-based forms of local resistance and politics, which we try to describe through concepts such as the commons, living space, environmental justice, and the right to the city beg to be revisited and re-discussed over Artvin’s struggle – and we must carry this geographical corner of the country, its story and struggle to the very heart of the corpus of the new activism that is slowly burgeoning. Perhaps one of the most valuable of these areas of debate is regarding how to name the protest in Artvin. At the root of environmental protest in Artvin lies a wealth of environmental assets and a disagreement about what to do with this wealth. This disagreement, in a sense, points to a problem of scales; the supposed needs of the national economy threaten the living conditions of the locals. The struggle waged by the people of Artvin, sitting on top of a natural resource (copper, and according to some, gold) belonging to the entirety of the nation but always having to suffer the pain rather than enjoy the gain is, in this sense, a struggle for environmental justice. While the slogan that has characterized the movement, “What lies on top of Artvin is more valuable than gold (what lies beneath it)” – using a pun on the Turkish word for gold that also means “what lies beneath” in this particular sentence construction – references precisely the different aspects of nature, the mine, even if tacitly, beseeches Artviners to make sacrifices for the welfare of the larger nation, but then leaves them alone with a burden they will struggle to bear. The people of Artvin try to upset this equation with questions such as “For whom?” and “At what cost?” The moment these questions are asked, it becomes necessary to interrogate the extraction economy based on infrastructure, energy, and mining, and scrutinize the close relations between political powers and infrastructure companies. At this point, the struggle inevitably takes on a critical identity that threatens the powers that be. On the other hand, the protest in Artvin is as much about the city and urban life as it is about the environment; and for this reason, it brings to mind the notion of the right to the city as well. Cerattepe is, after all, located only a couple of hundred meters above the Artvin city center, and as expressed in the momentous expert report prepared in 2014, as long as Cerattepe is being excavated for mines it is not possible to speak of the city of Artvin as we know it today. When what is at bay is the total destruction of a city, the struggle for Artvin becomes a claim for local heritage as much as it is about the right to the city and environmental justice; Artviners feel compelled to make a stand for their culture, history, and memories along with their city and natural environment.

Artvin allows us to think of yesterday’s foreign-funded extraction economy hand in hand with today’s brand of “home-grown and national” plunder of the commons

The fact that we get caught up in current events when talking about a twenty-five-year-old struggle in Artvin is a reminder that we need a historical perspective. For instance, Cengiz Holding, the notorious leader of the infrastructure universe, is not the first company that attempted to mine Cerattepe. Throughout the 1990s the people of Artvin waged a similar fight against Cominco Mining, and then the Canadian Inmet Mining in the first half of the 2000s – succeeding against both companies. As a result of tireless efforts, the Council of State revoked the mining permit given to the Canadian company in 2008, and Artvin took a deep breath. This relief lasted no more than two years, after which the region was once again opened to mining with the new mining act in 2010. Following a tender highly fraught with cronyism in 2012, the right to mine two giant expanses stretching over 4361 hectares in the upper reaches of the town of Artvin was accorded to the aptly named Özaltın (i.e. “pure gold”) company. Before long this company based in Artvin’s Arhavi handed over this right – as suspected by the people of Artvin – to a bigger player, Cengiz Holding, originating from the neighboring province of Rize. What these stories of “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours” come down to is: Artvin’s legacy of struggle grows in the face of both yesterday’s usual suspects and today’s; it allows us to think of yesterday’s foreign-funded extraction economy hand in hand with today’s brand of “home-grown and national” plunder of the commons.

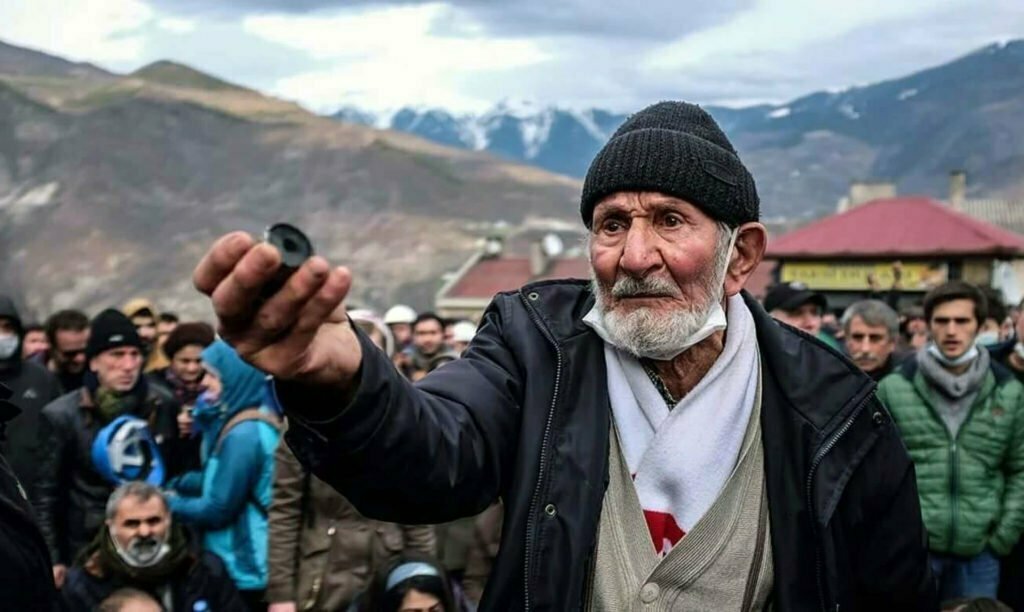

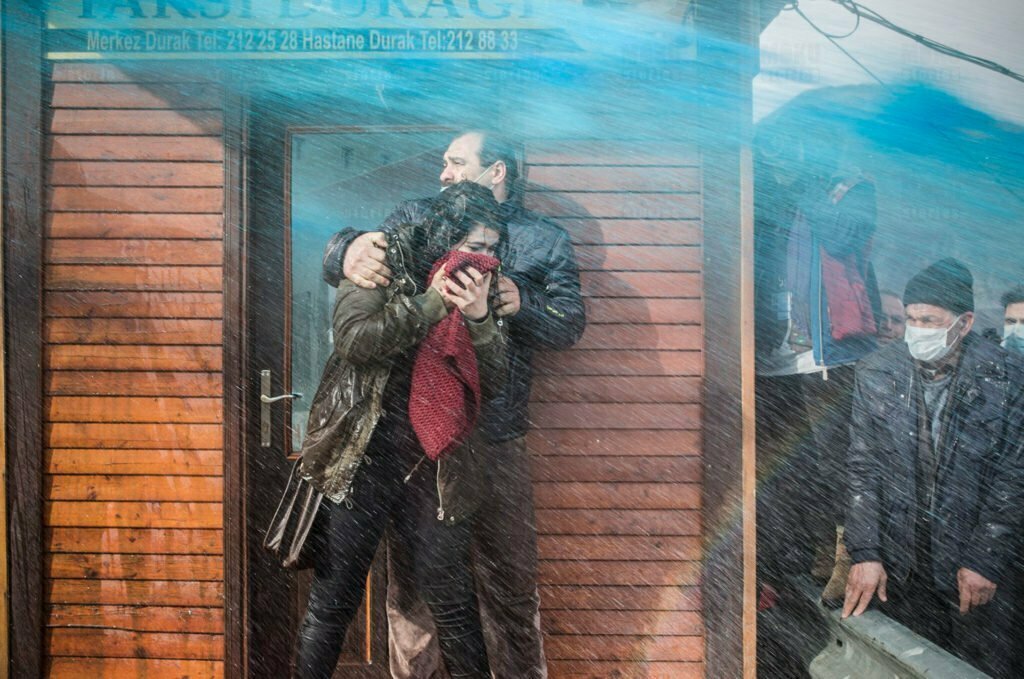

Another area of debate that renders the Artvin-Cerattepe movement particularly important pertains to the form of organization and methods of struggle adopted by local environmental movements. The Green Artvin Association (Yeşil Artvin Derneği), born in 1995, is the most successful iteration of a certain brand of struggle that may be termed mass environmentalism, that has a long line of examples in our country (with the Bergama rebellion and the Gerze resistance first to come to mind). On the one hand, the anti-mining battle is waged en masse with the participation of many different circles including men and women, the young and old, parents and children (and local businesses in particular), just as in many other urban and environmental struggles. On the other hand, the association is making a point of positioning the struggle as supra-political while also striving to establish contacts with as many organizations, institutions, and political parties as possible. This attitude has brought Green Artvin the love, respect, and sway of a successful local sports club in a small town. Although it is no secret that many of the members and leadership of the Green Artvin Association come from a leftist and social democrat background, Green Artvin manages to preserve the independence and impartiality of the city. And while it stays out of politics, it is not at all possible to call Green Artvin “apolitical.” Its ability to keep itself at a certain distance from commonplace political discourses and rivalries affords it unexpected political leeway and respectability. A result of this respectability is that the local authorities and city politics find themselves taking positions according to the association, or at least having to recognize the association’s position. Although there are questions about how this supra-political respectable status will be transferred to the national level, converted into macro-political economic demands, and eventually spread across the environmental movement (or whether it even should), Green Artvin presents a model as it is.

Despite all the pressures it faces, Artvin retains its position as one of the most important and fruitful fronts of the growing environmental struggle in the country

The most self-absorbed of environmental movements, those who don’t see beyond their own issues, who don’t care to trace incarnations of what befell their area across translocal networks are called “not-in-my-backyarders” (NIMBYs) and are shamed for this narrow outlook on the world. The Green Artvin Association may at times appear to act cautiously in order to keep the delicate balance that is perhaps a natural outcome of engaging in mass environmentalism. Yet, considering its methods and networks, it is not possible to classify Artvin’s struggle as a not-in-my-backyard type of movement that does not look beyond its own territory. Having served as a veritable school in the legal sense for new generation environmental lawyers, Artvin has always been an important reference point for other local environmental protests whether large or small. Especially in the Black Sea Region, one would be hard-pressed to find a struggle that Green Artvin hasn’t somehow come in contact with and provided legal assistance to, or an environmental action or meeting it hasn’t supported. In this regard, Artvin retains its position as one of the most important and fruitful fronts of the growing environmental struggle in the country.

Even though the ongoing mining operations in Artvin-Cerattepe are disappointing, it shouldn’t be forgotten that the movement has accumulated an important level of experience in the legal domain – the value of which shall become apparent in the future. The legal proceedings regarding mining in Artvin Cerattepe were completed in January 2015 for perhaps the umpteenth time and the people of Artvin had once again emerged victorious with an exemplary court ruling. The Rize Administrative Court had issued a verdict rarely encountered in environmental cases, using expressions in accordance with expert reports such as “[The Court] has come to the conclusion that engaging in mining operations shall render the province of Artvin unfit as a living space for its inhabitants, and that the existence of the mining project is not compatible with that of living spaces to be impacted by it and areas that are under preservation.” This verdict literally meant “Either Artvin or the mine; you cannot have both!” – and as such opposed the project categorically and constituted a permanent refusal. Taking into consideration that environmental cases are often won on procedural grounds and that this renders victories in environmental law highly temporary, this ruling of January 2015 was of revolutionary nature. It too, however, was disregarded – and the company applied to the Ministry with an EIA report that contained only a couple of minor changes (the details of which you shall read in this book) and received an all-too-swift approval. As the EIA revoked by the court of the first instance was still being reviewed by the higher court, the company pulled some strings and lo and behold, abracadabra and it managed to come back to Artvin with a positive EIA decision from the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization. All of this may be taken as proof of the dysfunctionality of the legal system. But it must be kept in mind that mining in Artvin was only possible in the atmosphere of over-securitization enabled by state of emergency conditions and that all the gains achieved throughout the legal process shall one day most definitely return to contribute to the struggle for Artvin as foundational elements.

Another valuable aspect of Artvin’s struggle is women’s definitive role and authority within the movement. It is not unusual for women to be at the frontlines of urban and environmental struggles. But the trouble is that this frontline role is limited to the day of protest, and women cannot go beyond (or are not thought of as more than) being visual elements that boost the sense of local belonging and legitimacy in spatial struggles. Although women, who bring legitimacy, dynamism, and authenticity to the day of protest with their visibility, are in fact on the immediate receiving end of environmental problems, they are generally relegated to the background in the daily undertakings of long-term struggles. The anti-mining movement centered around the Green Artvin Association is one of the rare examples that have overturned this pervasive state of affairs with the intensive role of women and women’s labor in decision-making and implementation mechanisms (for another example, cf. the resistance against the thermal power plant in Gerze). The figure of Nur Neşe Karahan, one of the twenty-five-year-long leaders of the movement, and her position is particularly important in terms of understanding what women may contribute to local struggles.

As much as the struggle against mining itself, Artvin also gives us clues as to how neoliberal developmentalism plays out in the provinces and peripheries of a nation, what kinds of mechanisms of consent it needs to survive, and what level of destruction it causes. Artvin is not only a province that draws investments for its mineral deposits. The town has also been the luckiest by far in terms of public investments per capita in the decade between 2002 and 2012. In this period the state spent an annual average of 387 TL in investments per citizen, while for the people of Artvin this figure sits at 2811 TL, meaning that ever since 2002, the people of Artvin have received about seven times as much attention as the average in Turkey… How wonderful, right? However, the Laz, Hemshin, Georgians, Bosha, and Turks of Artvin must not have appreciated all of these investments, this major leap in development, since they kept moving to metropolises such as Istanbul and Bursa to eke out a living. Today, 64% of Artvin’s registered population resides outside Artvin. In this period where public investments in the province are peaking, we see the population of Artvin both decline and age. For instance, while Artvin was an investment champion from 2007 to 2012, it lost an average of 5.4% of its population annually. Of course there will be those who argue that such a move for development will take time to show its positive effects. Yet for some reason, TurkStat (the Turkish Statistical Institute) has not partaken in this optimistic view: While it estimates that the population of Turkey will increase by 10% until the year 2023, it has predicted that the population of Artvin will shrink by 3% contrary to this trend.

When development is unjust, cities and regions are not uplifted; quite the contrary, they are reduced to sites of sacrifice

How is it that all of this investment, all of this effort to develop simply cannot keep the people of Artvin in their province? To find the reason for this sharp contradiction, we must of course look not to the ingratitude of the people of Artvin, but to the kind of public investment and the nature of the goal defined as “development” in Turkey. When development is unjust, cities and regions are not uplifted; quite the contrary, they are reduced to sites of sacrifice. The only reason why Artvin consistently remains on top of development and investment lists is its strong rivers that give it its character, streams that gush out in every corner, valleys carved out by them, and mountains containing valuable ores. A major portion of the public funding flowing into Artvin is allocated to infrastructure investments (particularly giant dams and the rebuilding of roads submerged by their reservoirs) that are dubious in terms of long-term contributions to Artvin’s local economy. Yet the irony here is that the conquest of this landscape doesn’t benefit the people of Artvin but the investor and those indirectly profiting from the investment – hence why the province never shifts from the position of losing its population to migration. The tragicomic aspect of this is that the electricity consumption per capita in Artvin, seemingly the receiving end of all of these dazzling energy investments, falls far below the national average, and the province ranks thirteenth from the bottom of the list of 81 provinces in terms of the percentage of households heated by radiators.

The people of Artvin, who today raise their voices against mines and small-scale HEPP investments, deeply regret having stayed silent against mega dams in the past. The sheer grandeur of the dams, the fact that they were being built for public benefit, and the horizon of development they gestured towards prevented many from taking a stance at the time. Today the discourse of development is met with much more suspicion in the region, with vocal complaints that all the talk about development did not result in any permanent structures to benefit the local area. Yes, we might as well consider Artvin, the regular address of public funding to be a symbol of the New Turkey with its many dams, viaducts, bridges, and mines. But if so, Artvin also indicates that development is unequal and unjust in this New Turkey.What kind of future awaits the city then? The first place to look at in this regard is local politics, which is expected to take on greater importance in the upcoming period all over Turkey. Despite the unfavorable fait accompli in Cerattepe, the results of the local elections on March 31, 2019, require us to contemplate new windows of opportunity. In 2014, the party in government had scored a major victory winning 7 out of 9 spots in Artvin, not only securing the province center but also dominating the entire province that is traditionally known as left-leaning. On the eve of March 31, this picture was completely reversed. All of Artvin including the provincial center – with the exception of the districts of Murgul and Yusufeli – were now painted in the colors of the opposition. Just as votes cast for the party in government didn’t equal to consent for destructive and polluting projects, it would not be accurate to read the change that took place in these local elections entirely as a victory of the anti-mining movement. Furthermore, it could be said that since the mining project is supported by the central government and judiciary, there is not much left to do in the legal sphere on the provincial level of Artvin to stop this from moving forward. A reminder could also be made that the local actor in control of the means of force is the Governor’s Office and that it is, for instance, the Governor who issues province-wide orders to ban demonstrations in order to silence the social opposition. Despite all of these facts, the fresh sense of legitimacy and boost of morale brought by the ballot could allow for more effective use of local governments in the upcoming period to keep the struggle for Cerattepe alive. The municipality may exercise its own authority and institutions to organize alternative environmental impact assessment processes, put its monitoring mechanisms to more effective use, set up an environmental justice monitoring department within its own body, or help amplify the voices of anti-mining protests by supporting creative festivals and actions. Bridging the gap between local politics and grassroots struggles and giving a platform to Artvin’s protest to amplify its voice, without forgetting that the struggle for Artvin is longwinded, the legal process is not entirely over, and the Cerattepe case is yet to be brought before the Constitutional Court will be some of the significant dynamics to shape the near future

Please go to this link to access the book titled “Public Interest Litigation for Spatial Justice: Cerattepe,” a product of the joint efforts of the Centre for Spatial Justice and the Green Artvin Association.